Saturday, January 8, 2011

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Buy Haiti Box Set and Donate To the Relief Effort!

The Alan Lomax Estate and Harte Recordings are dedicated to supporting earthquake relief efforts in Haiti.

The Alan Lomax Estate and Harte Recordings are dedicated to supporting earthquake relief efforts in Haiti.

To aid in that effort, the price of the ALAN LOMAX IN HAITI boxset will be reduced for a limited time to $115, with $15 going directly to local disaster relief organizations in Haiti. Topspin, Harte’s partner in the on-line selling world, has also agreed to donate a portion of its net profit from box set sales as well. You can buy the box here:

The Albert Schweitzer Hospital

http://hashaiti.org

American Jewish World Services

https://secure.ajws.org/site/Donation2?df_id=3460&3460.donation=form1

Doctors Without Borders

http://doctorswithoutborders.org/

Partners In Health

www.standwithhaiti.org/haiti < http://www.standwithhaiti.org/haiti>

Red Cross - http://www.redcross.org/

Every dollar counts. Please donate today and keep the lovely human beings of Haiti in your thoughts.

Monday, January 11, 2010

FREE TASTE - VOLUME 7 - FRANCILIA (QUEEN OF SONG)

Queen of Song

Between April 7th and 12th, 1937, in the town of Carrefour Dufort at Kay Moïse (the Moses compound), Alan and Elizabeth Lomax and Révolie

Polinice recorded a series of songs (and a short film) featuring a remarkable singer, a rèn chante (queen of song) named Francilia.

Polinice recorded a series of songs (and a short film) featuring a remarkable singer, a rèn chante (queen of song) named Francilia.

Unfortunately, Alan tells us little else about her, and we don’t even know her last name. However, the comfort level attained between the Lomaxes and Francilia is palpable, and the Francilia recordings are certainly some of the best, in terms of audio quality, in the entire collection. I would also point out the informal feeling of the recording sessions, with Francilia occasionally breaking out into laughter in reaction to people around her. People, truck

horns, and animals are often heard in the background.

Most of Francilia’s songs are ceremonial songs from Vodou. In this, her rendition of them on this volume is a bit artificial, because they would generally be heard in the ounfò with the ounsi-s joining the choruses or refrains. The call-and-response form of Vodou songs is sometimes captured in phrases such as voye–ranmase (throw out–pick up, i.e. call–response). With

a chorus responding to her, Francilia would no doubt be freer in improvising or varying her lead vocals. In one examples heard in this volume, however, a small group of friends joins Francilia to serve as her chorus. of rara songs are typically called sanba-s; those of konbit-s (work brigades),

sanba, or simidò. Song leaders in Vodou congregations may be called laplas kongo, oundjènikon, or (if female) rèn chante.

please enjoy the music of Francilia.

Thursday, December 17, 2009

The Road To Haiti by Gage Averill

Gage Averill is a professor of history and culture at the University Of Toronto. He is the premier scholar on Haiti and the person responsible for curating the ALAN LOMAX IN HAITI music portion of the ALAN LOMAX IN HAITI boxset, writing the notes, and translating many of the songs. He will be talking on FORUM this morning, KQED radio, at 10 am PST....

David Katznelson, our producer, asked how I got involved in Haiti; probably the question I’ve been asked most over the last twenty plus years. After working for some years as a tenant organizer in low income housing projects and then driving a tractor for an apple orchard – all the while I was playing Irish and Latin music – I went back to school to get a BA in ethnomusicology in the early 1980s, and that led to a grant to pursue graduate studies. For a class assignment I analyzed the music of rara bands in Haiti, and became interested in pursuing rara as a dissertation subject. But my research grant to study rara in Haiti in 1986 was put on hold by the Fulbright Fellowships when the rebellion against the Duvalier dictatorship broke out. So my back-up project became a study of Haitian popular music, which would let me work primarily in the urban areas of Haiti. I left first for the Haitian community of Miami and then Haiti in 1987. I began a side career as a journalist of Haitian music, and wrote the column Haitian Fascination for 8 years in The Beat Magazine, but I also continued my research, traveling between Haiti and the overseas Haitian communities for much of a decade. Over the time that I’ve worked in Haiti, I’ve been an election observer for the Organization of American States, organized festivals, prepared radio shows, written liner notes for a score of albums. I’ve marched in a band at carnaval, played with rara groups, gigged with konpa bands, attended week-long Vodou ceremonies, and traveled over much of Haiti from Cap Haïtien to Pestel in the Southwest. My engagement with Haitian music and with so many generous and patient Haitian friends and colleagues has inspired me and transformed me in profound ways.

Labels:

Alan Lomax In Haiti,

Forum,

Gage Averill,

Harte Recordings,

KQED

Sunday, December 13, 2009

VOODOO: The Little Understood Religion

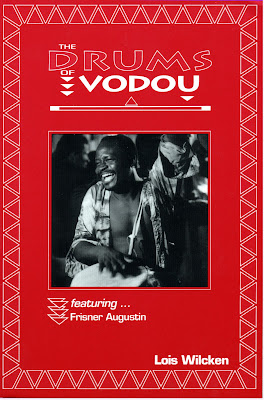

Scholar Lois Wilcken is the expert on Haitian Voodoo--literally writing the book on it. You can by the book here. Upon seeing the box set Alan Lomax In Haiti, Wilcken commented: Haiti, “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere” according to a tired cliché, re-surfaces as the Pearl of the Antilles through Alan Lomax’s compelling and comprehensive 1930s collection. Gage Averill and the project team have reached across seven decades to mine Haiti’s precious cultural gems, polish them, and put them on display. Haitianists beware, we have a new item on our “must” list!

Scholar Lois Wilcken is the expert on Haitian Voodoo--literally writing the book on it. You can by the book here. Upon seeing the box set Alan Lomax In Haiti, Wilcken commented: Haiti, “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere” according to a tired cliché, re-surfaces as the Pearl of the Antilles through Alan Lomax’s compelling and comprehensive 1930s collection. Gage Averill and the project team have reached across seven decades to mine Haiti’s precious cultural gems, polish them, and put them on display. Haitianists beware, we have a new item on our “must” list!Here is an excerpt from Wilcken's book Drums Of Vodou:

Vodou, commonly knows as “voodoo,” is a widely discussed but little understood religion. In this book author Lois Wilcken discusses politics in Haiti, anti-Vodou campaigns, plus the religious and cultural context of Vodou. But the chief contribution of this landmark book lies in its presentation and analysis of the sacred music of Haiti. Guided by the great Haitian master drummer Frisner Augustin, the author reveals the sacred rhythms of spirit possession. This book appeals to a wide range of percussionists, Caribbean music enthusiasts, scholars, and those interested in Vodou or neo-African religions.

Thursday, December 10, 2009

FREE TASTE #6 - VOLUME 6 - FLOWERS OF FRANCE

VOLUME 6 - FLOWERS OF FRANCE

ROMANCES, CANTICLES, AND CONTREDANSE

Without a doubt, what drew ethnographers to Haiti in the 1930s was the hope of encountering vigorous African traditions in the New World. Indeed, descendents of African slaves had preserved cultural expressions from African nations stretching from Angola through what is now Senegal. And yet the legacy of French colonization was also in evidence everywhere. Alan Lomax

encountered many of these French legacies, not just in the elite arts of urban Haitians, but in rural contredanses, in the canticles sung before Vodou ceremonies, and in children’s game songs in small towns around Haiti (see Volume 5, Pou Timoun-yo: Music By and For Children for examples of the latter). These vestiges of European expressive culture have not fared well in

the Haiti of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and some are extremely rare in Haiti today.

Most of the romances Lomax recorded, many of them by a group of musicians he called Louis and his Men (led by Louis Forvilice) are in archaic forms of French, or in a mix of archaic French and Haitian Kreyòl. Unfortunately, Lomax left many of these recordings untitled, and he left no

notes concerning the group or its songs. All in all, translating these songs proved to be extremely difficult, and I’ve had to leave many of them out and provide only skeletal lyrics for others.

This volume also explores another European survival, the music of Haitian contredanse. These examples feature a contredanse ensemble called the Sosyete Viyolon (Violin Society) with a folk violin as the lead melodic instrument, backed by a small percussion ensemble. Folk fiddles are still to be found in some areas of Haiti (ethnomusicologist David Yih recorded an ensemble near Les Cayes that used one in the 1990s, and I have recorded contredanse ensembles that use a fif or wooden flute instead). The contredanse was an import into the French courts from English country dances, and it became a hugely popular dance in France of the 1700s. It incorporated a number of choreographic figures for group dancing, which were typically called out by a dancing master. These contredanses, popularized in the colonies, survived colonialism around the Caribbean and spawned a number of popular dances from the couples sections of the figures (méringue and danzón, for example).

Finally, the recordings conclude with a short set of cantiques from those performed at the start of a Vodou Seremoni at the temple of an ougan named Ti-Kouzen in Carrefour Dufort on Easter Friday. These were given no titles and there is no mention of them in Lomax’s journals, but they are haunting and lovely.

Please enjoy this taste from Volume 6

(it can take a few moments to upload...please be patient)

ROMANCES, CANTICLES, AND CONTREDANSE

Without a doubt, what drew ethnographers to Haiti in the 1930s was the hope of encountering vigorous African traditions in the New World. Indeed, descendents of African slaves had preserved cultural expressions from African nations stretching from Angola through what is now Senegal. And yet the legacy of French colonization was also in evidence everywhere. Alan Lomax

encountered many of these French legacies, not just in the elite arts of urban Haitians, but in rural contredanses, in the canticles sung before Vodou ceremonies, and in children’s game songs in small towns around Haiti (see Volume 5, Pou Timoun-yo: Music By and For Children for examples of the latter). These vestiges of European expressive culture have not fared well in

the Haiti of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and some are extremely rare in Haiti today.

Most of the romances Lomax recorded, many of them by a group of musicians he called Louis and his Men (led by Louis Forvilice) are in archaic forms of French, or in a mix of archaic French and Haitian Kreyòl. Unfortunately, Lomax left many of these recordings untitled, and he left no

notes concerning the group or its songs. All in all, translating these songs proved to be extremely difficult, and I’ve had to leave many of them out and provide only skeletal lyrics for others.

This volume also explores another European survival, the music of Haitian contredanse. These examples feature a contredanse ensemble called the Sosyete Viyolon (Violin Society) with a folk violin as the lead melodic instrument, backed by a small percussion ensemble. Folk fiddles are still to be found in some areas of Haiti (ethnomusicologist David Yih recorded an ensemble near Les Cayes that used one in the 1990s, and I have recorded contredanse ensembles that use a fif or wooden flute instead). The contredanse was an import into the French courts from English country dances, and it became a hugely popular dance in France of the 1700s. It incorporated a number of choreographic figures for group dancing, which were typically called out by a dancing master. These contredanses, popularized in the colonies, survived colonialism around the Caribbean and spawned a number of popular dances from the couples sections of the figures (méringue and danzón, for example).

Finally, the recordings conclude with a short set of cantiques from those performed at the start of a Vodou Seremoni at the temple of an ougan named Ti-Kouzen in Carrefour Dufort on Easter Friday. These were given no titles and there is no mention of them in Lomax’s journals, but they are haunting and lovely.

Please enjoy this taste from Volume 6

(it can take a few moments to upload...please be patient)

FREE TASTE #6 - Disc 6 - FLOWERS OF FRANCE

VOLUME 6 - FLOWERS OF FRANCE

ROMANCES, CANTICLES, AND CONTREDANSE

Without a doubt, what drew ethnographers to Haiti in the 1930s was the

hope of encountering vigorous African traditions in the New World. Indeed,

descendents of African slaves had preserved cultural expressions from African

nations stretching from Angola through what is now Senegal. And yet the

legacy of French colonization was also in evidence everywhere. Alan Lomax

encountered many of these French legacies, not just in the elite arts of

urban Haitians, but in rural contredanses, in the canticles sung before Vodou

ceremonies, and in children’s game songs in small towns around Haiti (see

Volume 5, Pou Timoun-yo: Music By and For Children for examples of the

latter). These vestiges of European expressive culture have not fared well in

the Haiti of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and some are extremely

rare in Haiti today.

Most of the romances Lomax recorded, many of them by a group of

musicians he called Louis and his Men (led by Louis Forvilice) are in

archaic forms of French, or in a mix of archaic French and Haitian Kreyòl.

Unfortunately, Lomax left many of these recordings untitled, and he left no

notes concerning the group or its songs. All in all, translating these songs

proved to be extremely difficult, and I’ve had to leave many of them out and

This volume also explores another European survival, the music of Haitian contredanse.

These examples feature a contredanse ensemble called the Sosyete Viyolon (Violin Society) with a folk violin as the lead melodic instrument, backed by a small percussion ensemble. Folk fiddles are still to be found in some areas of Haiti (ethnomusicologist David Yih recorded an ensemble

near Les Cayes that used one in the 1990s, and I have recorded contredanse ensembles that use a fif or wooden flute instead). The contredanse was an import into the French courts from English country dances, and it became a hugely popular dance in France of the 1700s. It incorporated a number of choreographic figures for group dancing, which were typically called out by a dancing master. These contredanses, popularized in the colonies, survived colonialism around the Caribbean and spawned a number of popular dances from the couples sections of the figures (méringue and danzón, for example).

Finally, the recordings conclude with a short set of cantiques from those performed at the start of a Vodou Seremoni at the temple of an ougan named Ti-Kouzen in Carrefour Dufort on Easter Friday. These were given no titles and there is no mention of them in Lomax’s journals, but they are haunting and lovely.

Please enjoy this taste from Volume 6

(it can take a few moments to upload...please be patient)

ROMANCES, CANTICLES, AND CONTREDANSE

Without a doubt, what drew ethnographers to Haiti in the 1930s was the

hope of encountering vigorous African traditions in the New World. Indeed,

descendents of African slaves had preserved cultural expressions from African

nations stretching from Angola through what is now Senegal. And yet the

legacy of French colonization was also in evidence everywhere. Alan Lomax

encountered many of these French legacies, not just in the elite arts of

urban Haitians, but in rural contredanses, in the canticles sung before Vodou

ceremonies, and in children’s game songs in small towns around Haiti (see

Volume 5, Pou Timoun-yo: Music By and For Children for examples of the

latter). These vestiges of European expressive culture have not fared well in

the Haiti of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and some are extremely

rare in Haiti today.

Most of the romances Lomax recorded, many of them by a group of

musicians he called Louis and his Men (led by Louis Forvilice) are in

archaic forms of French, or in a mix of archaic French and Haitian Kreyòl.

Unfortunately, Lomax left many of these recordings untitled, and he left no

notes concerning the group or its songs. All in all, translating these songs

proved to be extremely difficult, and I’ve had to leave many of them out and

provide only skeletal lyrics for others.

This volume also explores another European survival, the music of Haitian contredanse.

These examples feature a contredanse ensemble called the Sosyete Viyolon (Violin Society) with a folk violin as the lead melodic instrument, backed by a small percussion ensemble. Folk fiddles are still to be found in some areas of Haiti (ethnomusicologist David Yih recorded an ensemble

near Les Cayes that used one in the 1990s, and I have recorded contredanse ensembles that use a fif or wooden flute instead). The contredanse was an import into the French courts from English country dances, and it became a hugely popular dance in France of the 1700s. It incorporated a number of choreographic figures for group dancing, which were typically called out by a dancing master. These contredanses, popularized in the colonies, survived colonialism around the Caribbean and spawned a number of popular dances from the couples sections of the figures (méringue and danzón, for example).

Finally, the recordings conclude with a short set of cantiques from those performed at the start of a Vodou Seremoni at the temple of an ougan named Ti-Kouzen in Carrefour Dufort on Easter Friday. These were given no titles and there is no mention of them in Lomax’s journals, but they are haunting and lovely.

Please enjoy this taste from Volume 6

(it can take a few moments to upload...please be patient)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)