Thursday, December 17, 2009

The Road To Haiti by Gage Averill

Sunday, December 13, 2009

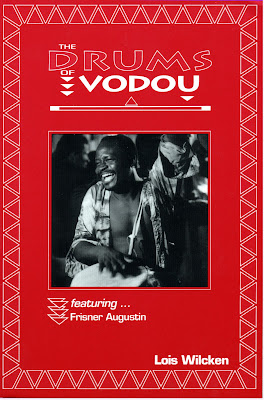

VOODOO: The Little Understood Religion

Scholar Lois Wilcken is the expert on Haitian Voodoo--literally writing the book on it. You can by the book here. Upon seeing the box set Alan Lomax In Haiti, Wilcken commented: Haiti, “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere” according to a tired cliché, re-surfaces as the Pearl of the Antilles through Alan Lomax’s compelling and comprehensive 1930s collection. Gage Averill and the project team have reached across seven decades to mine Haiti’s precious cultural gems, polish them, and put them on display. Haitianists beware, we have a new item on our “must” list!

Scholar Lois Wilcken is the expert on Haitian Voodoo--literally writing the book on it. You can by the book here. Upon seeing the box set Alan Lomax In Haiti, Wilcken commented: Haiti, “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere” according to a tired cliché, re-surfaces as the Pearl of the Antilles through Alan Lomax’s compelling and comprehensive 1930s collection. Gage Averill and the project team have reached across seven decades to mine Haiti’s precious cultural gems, polish them, and put them on display. Haitianists beware, we have a new item on our “must” list!Thursday, December 10, 2009

FREE TASTE #6 - VOLUME 6 - FLOWERS OF FRANCE

ROMANCES, CANTICLES, AND CONTREDANSE

Without a doubt, what drew ethnographers to Haiti in the 1930s was the hope of encountering vigorous African traditions in the New World. Indeed, descendents of African slaves had preserved cultural expressions from African nations stretching from Angola through what is now Senegal. And yet the legacy of French colonization was also in evidence everywhere. Alan Lomax

encountered many of these French legacies, not just in the elite arts of urban Haitians, but in rural contredanses, in the canticles sung before Vodou ceremonies, and in children’s game songs in small towns around Haiti (see Volume 5, Pou Timoun-yo: Music By and For Children for examples of the latter). These vestiges of European expressive culture have not fared well in

the Haiti of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and some are extremely rare in Haiti today.

Most of the romances Lomax recorded, many of them by a group of musicians he called Louis and his Men (led by Louis Forvilice) are in archaic forms of French, or in a mix of archaic French and Haitian Kreyòl. Unfortunately, Lomax left many of these recordings untitled, and he left no

notes concerning the group or its songs. All in all, translating these songs proved to be extremely difficult, and I’ve had to leave many of them out and provide only skeletal lyrics for others.

This volume also explores another European survival, the music of Haitian contredanse. These examples feature a contredanse ensemble called the Sosyete Viyolon (Violin Society) with a folk violin as the lead melodic instrument, backed by a small percussion ensemble. Folk fiddles are still to be found in some areas of Haiti (ethnomusicologist David Yih recorded an ensemble near Les Cayes that used one in the 1990s, and I have recorded contredanse ensembles that use a fif or wooden flute instead). The contredanse was an import into the French courts from English country dances, and it became a hugely popular dance in France of the 1700s. It incorporated a number of choreographic figures for group dancing, which were typically called out by a dancing master. These contredanses, popularized in the colonies, survived colonialism around the Caribbean and spawned a number of popular dances from the couples sections of the figures (méringue and danzón, for example).

Finally, the recordings conclude with a short set of cantiques from those performed at the start of a Vodou Seremoni at the temple of an ougan named Ti-Kouzen in Carrefour Dufort on Easter Friday. These were given no titles and there is no mention of them in Lomax’s journals, but they are haunting and lovely.

Please enjoy this taste from Volume 6

(it can take a few moments to upload...please be patient)

FREE TASTE #6 - Disc 6 - FLOWERS OF FRANCE

ROMANCES, CANTICLES, AND CONTREDANSE

Without a doubt, what drew ethnographers to Haiti in the 1930s was the

hope of encountering vigorous African traditions in the New World. Indeed,

descendents of African slaves had preserved cultural expressions from African

nations stretching from Angola through what is now Senegal. And yet the

legacy of French colonization was also in evidence everywhere. Alan Lomax

encountered many of these French legacies, not just in the elite arts of

urban Haitians, but in rural contredanses, in the canticles sung before Vodou

ceremonies, and in children’s game songs in small towns around Haiti (see

Volume 5, Pou Timoun-yo: Music By and For Children for examples of the

latter). These vestiges of European expressive culture have not fared well in

the Haiti of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and some are extremely

rare in Haiti today.

Most of the romances Lomax recorded, many of them by a group of

musicians he called Louis and his Men (led by Louis Forvilice) are in

archaic forms of French, or in a mix of archaic French and Haitian Kreyòl.

Unfortunately, Lomax left many of these recordings untitled, and he left no

notes concerning the group or its songs. All in all, translating these songs

proved to be extremely difficult, and I’ve had to leave many of them out and

This volume also explores another European survival, the music of Haitian contredanse.

These examples feature a contredanse ensemble called the Sosyete Viyolon (Violin Society) with a folk violin as the lead melodic instrument, backed by a small percussion ensemble. Folk fiddles are still to be found in some areas of Haiti (ethnomusicologist David Yih recorded an ensemble

near Les Cayes that used one in the 1990s, and I have recorded contredanse ensembles that use a fif or wooden flute instead). The contredanse was an import into the French courts from English country dances, and it became a hugely popular dance in France of the 1700s. It incorporated a number of choreographic figures for group dancing, which were typically called out by a dancing master. These contredanses, popularized in the colonies, survived colonialism around the Caribbean and spawned a number of popular dances from the couples sections of the figures (méringue and danzón, for example).

Finally, the recordings conclude with a short set of cantiques from those performed at the start of a Vodou Seremoni at the temple of an ougan named Ti-Kouzen in Carrefour Dufort on Easter Friday. These were given no titles and there is no mention of them in Lomax’s journals, but they are haunting and lovely.

Please enjoy this taste from Volume 6

(it can take a few moments to upload...please be patient)

Thursday, December 3, 2009

FRESH OFF THE PRESSES! THE BOX SETS HAVE ARRIVED!

Get your copy of ALAN LOMAX IN HAITI now! These are going fast, so get your copy today.

BUY BOX SET - $129.99 + shipping/handling:

BUY HAITI BOX SET

Monday, November 9, 2009

FREE TASTE # 5

for one or more children often arranged with a wealthier relative or even a stranger to “adopt” the child as an unpaid household laborer, called a rèstavèk (from the French rester avec, to stay with). Although children in Haiti have always been dearly cherished, parenting regimens tended to be very strict, often employing repercussions as severe as corporal punishment (the use of

a cat-o’-nine-tails, called matinèt or rigwaz in Kreyòl, was common). These harsh realities of childhood resulted in the frank tone of many Haitian children’s songs, and yet there is also much joy in these songs, offering a glimpse into a world of play and creativity that is usually hidden from adult eyes.

These recordings explore the contradictory spaces of childhood: Boy Scout songs, gentle lullabies, fear-tinged songs of lougawou-s (werewolves) and child-eating witches, counting songs for instruction, game songs for passing rocks and splashing in water, round songs for circle dances, and songs that veer from the innocent and childlike to trespass on adult themes or betray an unfortunate familiarity with hardship.

Please enjoy the music from Volume 5 - Children's Songs

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

FREE TASTE - VOLUME 4

RARA: VODOU IN MOTION

Four majors marched together at the head of the band. Thomar danced along, crouching, yellow shirt, calling the band over his shoulder, the president at his side. The two coronels with their whips behind the four majors, their batons flashing in the sun. Behind them the vaxines, and behind them the mob, singing and dancing. Clouds of dust rising up from beneath their feet.

Rara may have started during the colonial period as a French celebration called Carnaval Carême (Easter Carnaval), a week of celebration to end Lent and to lead into Easter; the practice of playing for patrons en route may be a holdover from the plantation-era practice of playing for colonial masters. Indeed, an early alternative name for rara, lwalwadi, may be a corruption of

“la loi di”, meaning “the law allows,” referring to the permission in the Code Noir of Napoleon for slave celebrations of this nature.

Sunday, November 1, 2009

NOTES FROM A RADA CEREMONY (from Alan's Journal)

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

ALAN'S REPORT TO THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS

"I have looked about enough to be sure this is the richest and most virgin field I have ever worked in. I hear fifteen or twenty different street cries from my hotel window each morning while I dress.

The men sing satirical ballads as they load coffee on the docks. Among the upper-class families many of the old French ballads have been preserved. The meringue, the popular dance of polite society here, is quite unknown in America and has its roots in the intermingling of the Spanish and French folk-traditions. The orchestras of the peasants play marches, bals, blues, meringues. Then mama and papa and kata tambours officiate at as many kinds of dances ⎯ the congo, the Vodou, and the mascaron. Then there seem to be innumerable cante-fables [oral tales punctuated by songs or rhymes performed by the audience]. Each of these categories comprise, so I am informed, literally hundreds of melodies ⎯ French, Spanish, African, mixtures of the three. The radio and the sound movie and the phonograph record have made practically no cultural impression, so far as I can discover, except among the petit-bourgeois of the coastal cities. And American jazz is hardly known here except among the rich who have visited America. Composition, by which I mean folk composition, is still very active. So I think I can say that unless a piece of sky falls on my head, this trip will mean some beautiful records for the Library’s collection."

The men sing satirical ballads as they load coffee on the docks. Among the upper-class families many of the old French ballads have been preserved. The meringue, the popular dance of polite society here, is quite unknown in America and has its roots in the intermingling of the Spanish and French folk-traditions. The orchestras of the peasants play marches, bals, blues, meringues. Then mama and papa and kata tambours officiate at as many kinds of dances ⎯ the congo, the Vodou, and the mascaron. Then there seem to be innumerable cante-fables [oral tales punctuated by songs or rhymes performed by the audience]. Each of these categories comprise, so I am informed, literally hundreds of melodies ⎯ French, Spanish, African, mixtures of the three. The radio and the sound movie and the phonograph record have made practically no cultural impression, so far as I can discover, except among the petit-bourgeois of the coastal cities. And American jazz is hardly known here except among the rich who have visited America. Composition, by which I mean folk composition, is still very active. So I think I can say that unless a piece of sky falls on my head, this trip will mean some beautiful records for the Library’s collection."

Monday, October 26, 2009

THE HAITI BOX SET - FREE TASTE #3

Click on the text box below to enjoy the music of Carnaval:

(please be patient...this email widget can take a few moments to load on certain platforms)

Monday, October 12, 2009

The Haiti Box Set - Free Taste #2

"During his initial month in Haiti, Alan Lomax fell in love with the rough-hewn music of small ensembles that he called malinoumbas groups (sometimes called manoubas or manoumba) after the name of the large boxlike "thumb piano" on which a player sits and plucks metal tongues suspended over a sound hole. Along with malinoumba, these rustic ensembles typicaly feature one- or two-string instruments (a guitar and/or a four-string banza banjo sometimes a twa or trois, a stringed instrument equivalent to the Cuban tres, with three courses of double strings, a tchatcha (gourd rattle, similar to the Cuban maracas) a tanbou (barrel drum played by hands), bwa (percussion sticks comparable to the Cuban claves) and sometimes an accordion.

These same ensembles go by many names; sometimes they're simply called ti bann (little ensembles) or twoubadou groups."

Click on the text box below to enjoy the music of the Troubadors:

(please be patient...this email widget can take a few moments to load on certain platforms)

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

A Rara Band’s Search For Home Pt. 2

...but there was still the problem of defining rara - and more specifically finding footage that could bring its origins to life. A year and a half of archival research had provided some clues: Maya Deren’s Divine Horseman includes some gorgeous shots of rara dancing and vaksin playing. Anthropologists George Eastman Simpson and Melville and Francis Herskovitz documented both a few stunning processions, as well as many of the rites and rituals of village life from which the ritual or rara sprang. Other leads were more elusive: we heard a rumor from a scholar that Katherine Dunham had filmed rara’s in her graduate studies research.

After a year and a half of emails, phone calls and written requests, we were finally given access to the footage only to discovered that 1) while Dunham was a genius at writing, dance, and scholarship, she wasn’t particularly gifted at holding a camera steady, and 2) she did not in fact ever film more than a few seconds of barely-on-screen rara musicians.

Gage Avril, the editor of this box set, first tipped me off to the Lomax’s footage of rara (which the Lomax Archive was generous and helpful in providing). When I watched the footage I was immediately struck by the many remarkable paradoxes. The first was that the footage, shot in 1936, is in full color! (In fact, it became a challenge to convince audiences that the footage was as old as it is.)

The second paradox was that while it was one of the earliest recordings of rara in the field - it was also largely faked. As I’d learned from Dr. Avrill, the rara was staged for the camera, outside of traditional rara season, and within the confines of a private compound or “lakou.” The problem was that there were no public raras to film, since the local Catholic Church was in the midst of one of its periodic vodou purges, in which public ceremonies were banned, drums and ritual objects were burned, and by some accounts, vodou priests were occasionally killed.

So the footage didn’t have the usual chaos or a rara procession, where its nearly impossible to figure out what’s going on or where to look.. Instead a few musicians, dancers and singers made few orderly marches and turns, dancing, jumping and flailing arms along the way. (Lomax’s team could record film or audio, but not both at the same time, so it was impossible to tell which songs were actually being played). Yet ironically, there was something in the staged exuberance of the footage that communicates the spirit of rara better than almost any footage I’d found. It was as if, knowing that the audio wasn’t being recorded, the musicians were giving the camera a silent charade of what rara was supposed to sound like. When we’d show the footage to audiences in rough-cut screenings, they always love the clips, and comment on its infectious energy. It ended up being one of the most compelling documents of rara we’d found.

In the end, just as it was impossible to define rara, we realized it was impossible to find footage which could show what a “true” rara looked like. The best we could do was to look to incredible documents like Lomax’s films for flickering hints about the origins, the meanings, and the spirit of the music which is still moving and electrifying audiences decades later and thousands of miles away.

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

A Rara Band’s Search For Home Pt. 1

A Rara band’s search for home, a filmmaker’s search for archival footage

A Rara band’s search for home, a filmmaker’s search for archival footage

We also found troves of home-movies shot by the band’s fans since its founding in 1990. This stack of beat-up VHS and Hi-8 tapes traced the band’s jubilant creation one afternoon after Aristide’s first election, through the politicization of the band during the “Haitian-American Civil Rights Movement”, through the band’s own internal coup – when young hip-hop inspired musicians arrived from Haiti with a vastly different conception of the music. In each stage, hundreds of years of history, stigma, politics and identity are battled out in the haunting sounds of tin kone horns and bamboo vaksins.

But there was still the problem of defining rara - and more specifically finding footage that could bring its origins to life ......."

Monday, September 14, 2009

A Vodou Ceremony Pt. 2

A Vodou Ceremony Pt. 2

Possession by the Loi

...then a violent and frenzied dance begins — the hips and shoulders shaking, wiggling, shivering, and vibrating in a fashion impossible for a person in a normal physical state. Later Gran Erzulie enters into the body of a young girl who had seemed before to be made out of sections of willow branches; a completely soft young adolescent face over a body so pliant and fine that it could not stand straight but let every bone take its own separate angle, the whole body akimbo.

Now this pliant body grew suddenly old, the legs were bent and bowed inward with rheumatism and the belly was sucked up with pain and fatigue under the withered breast. A continual low murmur of groans and whines came from the twisted lips as the other dancers jostled her.

Then the drummer, Ciceron [Marseille], whom I believe carries all the loi in his thin, old hunched shoulders that make the mama drum growl and roar, called to the loi to dance, and Simbi and Gran Erzulie seemed to be shaking themselves to pieces, the first in his male and the second in her old female fashion. This dance went on growing more and more violent until the mamaloi called for a mason, which is the signal for the departure of spirits. At the end of this dance, both Simbi and Gran Erzulie swooned separately on the floor in each others’ arms, those two young bodies curved against one another in a sort of trance of exhaustion. All this time, of course, there had been other loi in the women present, but the loi themselves, the inspired women, had given place way and precedence to the two I have described. Presently, as the singing recommenced, the body that had held Simbi dragged itself off into a corner and went to sleep with its head in its arms The habitation of Gran Erzulie, however, only leaned against the wall for a few moments and soon was back in the dance again.

Monday, August 31, 2009

A VODOU CEREMONY Pt. 1

The Mombo and her assistant were in no hurry about lighting the candles on the altar from the oil lamp that is kept burning always on the floor of the assembly room. The doors were kept shut, or partially so, during the lighting of the candles, in one of which four young women who are being prepared for baptism participated.

At last, however, the Mombo began to dance. She whirled slowly about the rooms a few times, swaying and bowing, her feet as precise as a première ballerina. She made libation before each drum. Presently, after she had danced for ten minutes, and she is by far the most graceful and charming dancer I had so far seen, the others began. Each one in turn kissed the ground before the drums, the others singing, the drums beating the Jean Valou rhythm, and then bowed and kissed the ground before the Mombo's feet.

Back in the main room again the drums were beginning to pull the loi into the hearts of the worshippers. A tall young woman in white with a red head rag and a loose and silly face was Simbi. A possessed person (generally) begins by staggering about the room on one leg, almost but never quite falling into the arms of the spectators. The motion is that of a person walking along the iron of a railroad track. Then a violent and frenzied dance begins....(to be continued)

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

Tracking Through Haiti: The 1937 Lomax Recordings in a New Millennium

One interesting aspect of the experience was that since the discs were copied in the order they were recorded, the whole field trip was relived, in a sense.

In one of the first recordings from this field trip, Alan Lomax can be heard expressing his doubts about his recording apparatus during a microphone test conducted somewhere in Port au Prince, Haiti. I heard his remarks on the first of some 300 aluminum discs that Library of Congress sound engineer Brad McCoy transferred digitally while I took notes from the other side of the turntable for nearly a month several years ago. The aluminum disc system employed for these Haitian recordings was indeed cumbersome and difficult, and this would be the last major field trip on which Alan employed it, switching soon thereafter to the new portable acetate disc cutters that made quieter and more sensitive recordings.

Clumsy as the old system was, Alan and Elizabeth Lomax had nevertheless made it work in an astounding array of unusual recording situations in the days from Christmas, 1936 through Easter, 1937 in Haiti. From lone singers to full dance orchestras; from the more polite steps of Port au Prince society to the high-energy rhythms of Mardi Gras drummers; from church services to voodoo ceremonies, they pushed the equipment to the limit. The twelve-inch aluminum discs they used for most of these recordings could only hold about five minutes of sound comfortably, but often, they simply had to hold more. On many discs, Brad and I saw that they had allowed the recording head to keep tracking to within barely an inch of the hole in the center of the disc. This reduced the fidelity and created untold technical headaches more than sixty years after the recordings were made, but in this way, a few seconds, perhaps even a full minute more of priceless documentary recording was accomplished

For more than seventy years, these recordings have lain in obscurity. I doubt if even a single scholar has listened to them all. They are not the only field recordings to have languished for decades, but I wonder if any field recording trip of this scope and importance ever sat on the shelf for so long. The recordings had little or no direct effect in their day, but they at least set a precedent and may have helped facilitate other important fieldwork undertaken for the Library of Congress over the next several years, including Melville and Francis Herskovits’s Brazilian recordings and Henrietta Yurchenco’s Mexican recordings. Now at last, they can reach Haiti and the rest of the world, and I’m very glad to no longer be one of the only people to have heard these precious discs.

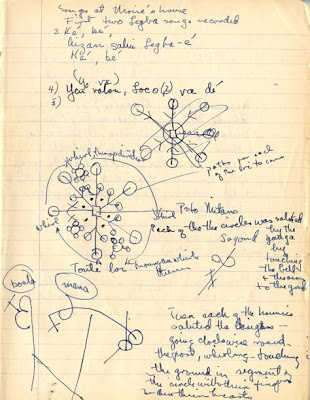

**The image in this post is of a disc sleeve of one of Alan's recordings including his notes.

Saturday, July 11, 2009

Haiti Trip Ephemera Pt. 1

....there are more items like this one to come!

....there are more items like this one to come!

Monday, July 6, 2009

“How the Haiti Project Came About” Pt. 2

...a separate Haiti series was clearly called for, although we knew that demanding sound engineering and cultural/ linguistic translation issues were involved which would make it a complex — and costly — undertaking of long duration. Borrowing funds from other budgets, we began by making faithful, high quality transfers from the original aluminum discs to DAT. We also enlisted the ethnomusicologist, Gage Averill, a specialist in Caribbean music, to re-catalog, compile, and annotate the recordings. Gage, who had just begun teaching at NYU at the time and was about to become a father, was nonetheless eager to listen to the whole lot, and soon came up with a thematic scheme for nine CDs, and over the next couple of years, sequences and notes for two.

Other projects pushed Haiti into the background, because three years later, sophisticated sound restoration technologies, capable of removing the hisses, pops, and crackles that n

early drowned out the recordings, were offered to us at an affordable price by the Magic Shop, our mastering studio.

early drowned out the recordings, were offered to us at an affordable price by the Magic Shop, our mastering studio.Meanwhile, we at the Association for Cultural Equity had embarked on a full-scale effort to disseminate and repatriate digital copies of Alan Lomax’s media documentation to their places of origin. Thus, rather than resurrect only those tracks selected for publication on CD (a mere fifteen percent of the collection), we elected to restore and pre-master the entire fifty hours, with the intention of repatriating them to Haiti. We would also make copies available to the Library of Congress and the Schomburg Center and offer samples of all tracks on the Association for Cultural Equity’s online catalog.

Enter David Katznelson of Harte Recordings. Jeffrey Greenberg brought Dave to us a couple of years ago to discuss issuing hidden treasures from the Lomax collections. We considered several possibilities, among them Haiti. Dave had been an A&R man at Warner Brothers, immersed in rock and pop, so it was a happy surprise when he offered to embrace the Haiti project and produce an attractively designed box set.

Dave’s enthusiasm for all aspects of the project reignited our own. Gage Averill and his Haitian colleagues returned to the demanding task of selecting and identifying songs, tracking down the meanings of obscure and obsolete forms of Kreyòl, transcribing and translating song lyrics, and writing notes. Ellen Harold began the months’ long process of transcribing and editing Alan Lomax’s handwritten diaries and letters. At the same time, work on the box supported our preparations for repatriating the full collection to Haiti.

In every respect, we wish this endeavor to be an hommage to the Haitian people. It is also a tribute to Alan Lomax and the Library of Congress for having had the foresight to undertake and support this project, which recognized African American culture as a distinctive network of affiliations extending far beyond the boundaries of the United States, and to and from Africa.

Anna L. Wood, Ph.D. is Director of the Association for Cultural Equity and the Alan Lomax Collections in New York City.

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

HAITI IN THE NEWS: Bill Clinton Named As Special Envoy On Haiti

Former U.S. President Bill Clinton will be named a U.N. special envoy on Haiti this week, sources close to the United Nations tell The Cable.

"I've been following this country for more than three decades," Clinton told the Miami Herald. "I fell in love with it 35 years ago when Hillary and I came here. I think I understand what its shortcomings have been but I've always believed most of its problems were not as some people suggested; cultural, mystical. I think they were subject to misgovernment. They were either oppressed or neglected and they never had the benefit of consistently being rewarded for effort in education, in agriculture, in industry and in any area. And, therefore, they were forced to become incredible, if you will, social entrepreneurs and to make the most of daily life... Tell the world Haiti is a good place to invest'."

“How the Haiti Project Came About” Pt. 1

The multifaceted Alan Lomax in Haiti stems from Lomax’s original work in the Caribbean in the mid–1930s and has been a long time coming. It spans the history of sound recording and playback technology of the last 75 years, and it is thanks to progress in this field that we can now listen in to Haitian worlds that no longer exist. Such advances make realizable the humanistic goals of cultural equity and cultural feedback that Alan Lomax ardently espoused, so that it is now possible to bring a generous selection from this rich collection to the public, and to return it whole to the Haitian people.

In the 1970s Alan Lomax spent several months at the Library of Congress going through the early recordings of African American and Afro-Caribbean folk song that he and his father, John A. Lomax, had made in the 1930s and ‘40s. The Black Pride Movement was still in full swing, and it was Lomax’s plan to bring to the movement an encyclopedic collection of what he regarded as among the fundamental sources of black culture and history in the Americas.

Alan mapped out a series of twelve LPs with the working title Treasury of Black Folksong (later Deep River of Song), which included music from eight states and the Bahamas — but which did not include Haiti, where he had worked in 1936–37, probably because it was acoustically challenging. As it happened, publication of Deep River was delayed until the late 1990s — fortunately so, in that acoustic science had by then leapt into the digital age. Whilst at the Library of Congress transferring sound for this series, Lomax Archive Sound Archivist Matthew Barton took a look at the Haiti collection and was astounded to find fifty hours of recordings — some 1,500 items — and hundreds of pages of field notes and correspondence that had scarcely been touched.

A separate Haiti series was clearly called for...(to be continued)

Monday, March 2, 2009

WELCOME TO OUR BLOG

ENJOY!!!!

100% Donation - 10 Songs - Alan Lomax in Haiti